Seeking distraction from World War II I’d confronted him last night, striking in cold vengeance by suddenly grabbing his collar and dislodging his boater, which fell into the street wobbling like a top. Recognizing me his eyes went from buttons to saucers and he shrieked like a porcupine. An amorous porcupine. They shriek a lot. Long story.

Anyway, I went in for a straight punch to the gut, but he fought like a girl, one with bricks in her gloves, his sissy slaps landing like a hailstorm of ball bearings, and I’d found myself nose cloudward, writhing on the sidewalk, brain reeling, watching my 1000 shares of Skymaster Gyrocopter Messaging sputter, spin, crash and explode, just like Skymaster’s real gyrocopters, all over again. The only message these crazy bamboo whirling gizmos ever really carried was “never buy stock in Skymaster Gyrocopter Messaging, particularly in October, 1929.”

So I’d retreated to the Rusty Hobnail for some tender hating care from Crumples the Bartender: the icy comfort of a familiar glower from the oyster-faced stare of a man who once served Ulysses S. Grant his morning quart of whiskey: bare-knuckle boxer in the 1880s, who’d played dirty. He’d kicked, bitten and snacked on opponents with fists like hard cheese, and was about as smelly. Old man now. People said that on seeing the newborn Crumples, Andrew Jackson promptly spit on him. He made the Sphinx look coltish. His mother once did unspeakable things for Napoleon the II involving a three-legged horse.

Never got along with anyone, which made bartending an interesting choice. He got on the wrong side of everyone. Mark Twain cuffed him in the ear. Teddy Roosevelt pulled a gun on him. Gentleman Jim once screamed endless, inventive and obscene insults at him for an entire week.

For Crumples, seeing me beaten, bruised and bleeding was like opening a Christmas present. He clapped his veiny hands and laughed out loud, a dry, joyless squeaking sound like repeatedly opening an ammunition box from The Crimean War.

I was looking at Crumples through the bottom of the glass to improve the view when a noise rose like a freight train slowly crushing an ice cream truck. I looked back to the stage to see a man in a kilt apparently strangling a vacuum cleaner: a desperate Okie folk musician with a defective Waziristani bagpipe who knew about as much about Scotland as your average African lungfish. The music was excruciating, the Okie’s fingers about as light as anvils, the lamps shaking in a ceaseless blast of celtic cacophony that put an odd smile on Crumples’ face, like a parenthesis had jumped off Mt. Shasta and died.

I could only grimace. I took what solace could be had in the familiar shambles of the bar; walls caked black with whale oil smoke and a couple of tab-skipping customer's skulls nailed on those walls, it was the last upside-down ship used as bar from back in the Forty-Niner days.

The Rusty Hobnail was not the kind of joint where you put folk musicians- unless you planned to put them in traction. It was a real San Francisco dive, tied fast on the wrong side of the tracks by a nickel-a-view villain in cape and top hat and with us all trapped in his moustache-brushed penny arcade plot. Too many four-flushing, thrice-boiled, two-bit half-lifes on the make, cops on the take and girls on the fake drooled on variously by fools, chumps and Nob Hill hobos raking it all in; and me amongst: Mack Brain, a once-solvent $10 a day ($15 on Saturdays) Detective and aspiring back-alley Doctor, hiding away from the War and the girls and the bad memories of fifteen or twenty friends I’d accidentally gotten killed, sending them out on hopeless attack hot-air balloon missions against Goering, selling them out to the Mob for beer money, stabbing them myself for some good reason I’m sure but which I couldn’t remember now, or poisoning them with a hastily-written prescription for poison. And that was just the people I liked.

So you go to the Rusty Hobnail to pickle all the hopes and dreams in your head until your brain is indistinguishable from the eggs in the big glass jar on the end of the greasy slab of oak bar- with 19th century barnacles still stuck to it, which Crumples absurdly polished with glee when he wasn’t fantasizing about beating your head in with far greater glee.

I was pickled good but not plenty. Life hurt like a sack of glass shards was giving you a Belgian massage. I’d even talked my girl- the wolf-whistlable Wobbly welder girl Petunia Mathelby- into going underground with a cover as a fascist-sympathizing cigarette girl to track down the notorious pro-Nazi pastry chef and traitorous ball player Stingy Wheels - my nemesis, a man so nemisiotic I could hardly turn a corner without feeling the beady stare of his malevolence on the hairs on my neck. It felt like a bunch of Nazi aphids crawling around, thinking my neck was Czechoslovakia. But now Petunia, my pretty little raven-haired Red - I hadn’t heard a peep out of her in weeks. And Stingy tended to leave bodies around more often than notes about his whereabouts. So I drank, and I brooded, and drank again, and listened to a country version of “Scotland Wha Hae” that made a hot air balloon assault against Schweinfurt sound like a turn around Lake Pleasant in a peddle-boat.

I praised all-Merciful Zoroaster when the pipe music ended as the piper passed out in a heap of plaid, falling face first into the beer-soaked sawdust on the floor. Maybe someone stabbed him. No one checked. I drained my Everclear and Orange, and Crumples just refilled the glass with a pinkish fluid that might have been Finnish Sloe Aquavit, or maybe freshly siphoned gas. I drained that too.

Then there was the sound of a washboard and fiddle tuning up. Crumples actually booked a whole band that didn't feature the hornpipe.

I looked them over. Wasn't much of band. Guitar, fiddle, washboard, and what appeared to be a steam-powered auto-harp, with a wooden pick arm and a tiny little engine. These guys staggered on in clothes that once were blue, or striped, or mattress covers, and had clearly steeped in so much mary-jane that they were just now remembering that their dreams were crushed. They picked up their instruments with the kind of enthusiasm you pick up a pick-ax in an chain gang, and warmed up their assault.

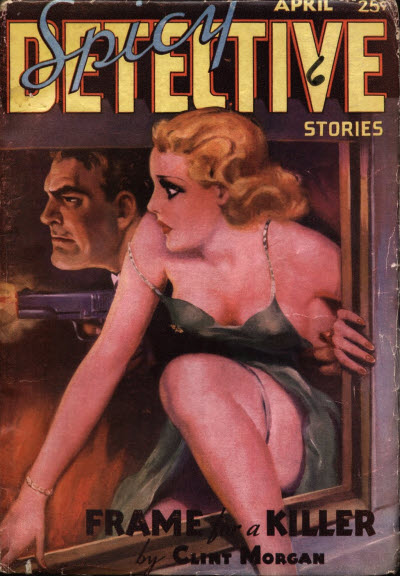

And then I saw The Blond, a real cool canary purposing to sing while backed by these Hobo Mozarts, a downtown dame in smart red silk number tighter than Winston Churchill during the Blitz, the kind of frail more dangerous than an overturned flaming railcar of hydrogen peroxide in an explosives showroom. She had steel blue eyes like a cold, clear day you see looking up from a glacial crevasse you'd just fallen into while distracted by a bombshell blond in a red silk number walking around a glacier. Long torso, long legs, looking softer than a pillow in a pudding bed, clear skin like a painting of a girl with clear skin, and lips bright red like a neon sign that read "Yes, and Yet No." Admittedly, there weren't a lot of signs like that. And not a lot of men up to handling a cherry tomato like that. Takes a light touch, like removing a bra with one hand that's wrapped around a gallon of nitroglycerin. But dangerous tomatoes were my kind of vegetable, or maybe fruit, if you're agriculturally pedantic joker who just got a job pissing me off. I grabbed my hat, drink, a semi-crushed pack of Luckys, the .38 with the Breughel engraving , and prepared to pour on the charm like cream on a strawberry shortcake.

"So where's the jug player, Toots?" I asked, offering a Lucky.

"Wallow here often?" she said in a sleek, stiletto voice that made you want to thank her for sliding in the blade between your ribs.

"You’re planning to sing in front of the Dust Bowl Philharmonic here?" I said, tossing a thumb their way.

Her nose wrinkled in such a way that it showed her displeasure and sucked my brain dry in one go.

But she took the Lucky, and looked at me sideways a little, expecting me to light it. I took an extra half-second taking in her angel face before I lit the cig, using the commemorative Red Star Zippo General Krushchev had given me when I located the captured Nazi plans that detailed the part in a Panzer's carburetor a small six-year old could sneak in and snap off in their hands. That lead to some guilt later when 8,000 six-year olds were sent in at the battle of Kursk.

"So, I hear you snoop around?" she asked.

"Come again?"

"You're a private dick, right Mister? They told me I could find you here. "

"Who?"

"Your girl. The high class dame at your office. I told her to buzz off or I'd cut her," she said. Hmm. That stiletto wasn't metaphorical.

"Wow. Thanks, Missy. Saves me a lot of trouble. Which girl are we talking about?”

If this conversation got anymore hard-boiled we could make egg-salad sandwiches for everyone at the wedding.

She stretched now, her long arms nearly touching the grimy ceiling, giving me a full blast of that dame-based weapon that breaks hearts, fells empires, and gets people looking through the Sears catalog for matching drapes. Stretching that soft, wriggly femininity to the high heavens was enough to make Jesus all mushy- and that wasn't Cricket.

“Some lady Psychiatrist, pretty girl, smart, stuck-up, you know, going through your case files.

“Lillian Gruber?”

“Beats me. She just had her Freudian Analysis Society Badge on.”

The Blond tossed her long hair back, shiny golden waves breaking over an unmitigated bare shoulder, her big ice blues a little sleepy, her mouth moist and lips just a little open. "I got a little proposition for ya, Mack," she said moving her flawless face towards my ear, so close to my cheek I could feel the heat off her smooth light skin, smell her scent – Victory in the Pacific, I think, going by the sweet coconut musk.

"Goahusdunafopgadsidafum?" I said.

"My name is Veronica D'Atlantique," she whispered in a voice sweet, soft, and low, like a cotton candy mattress. “Like the famous ocean,” she explained.

”My Name’s Mack Brain. Dr. Mack Brain.”

We were interrupted in this repartee by the truly incomparable sound of a steam-driven autoharp failing to be tuned. I looked over, and got a glimpse of two green eyes launching at me like marbles in a slingshot.

"Don't mind Shanky, he's kinda sweet on me," she said, curling herself around weightlessly so that I found my hand lightly on her waist. =

I looked at Shanky in his grubby coveralls working over the knobs to adjust the pressure to tune the steam-autoharp. He glared hot coals over the autoharp’s soundbox as slow swirls of steam rose from the tiny brass boiler.

I’d been in here fifteen minutes and someone else had joined the Kill Mack Brain Society, which was fast becoming the biggest organization in the Bay Area, short of the Brotherly Order of Free Beer and Cash Lovers.

“But you see,” she said with her finger walking up my arm, “I know something about you, Dr. Brain. “

I perked up, as much a tadpole in a pond full of Everclear can perk up. Babycakes had done her homework.

“Mack, right? Of the Chicago Brains?”

“And what’s it to you, Sugar? Maybe and maybe not. Hasn’t everyone got a family name they’re ashamed of?”

“Not just any schlub’s family, Doc… Take a look at this. City Directory: Brain Life Insurance,” she said, perking me up out of the pond, and she kept going: Brain Coal of California. Brain Cold Meat Packers. Brain Bronze Fittings. Brain Drug. Brain Financial. You want me to keep going through the rest of the Alphabet?

“I thought it was a coincidence.” I looked at her funny, through a greenish fog caused by enormous dollar signs floating before my eyes.

“Listen, Brain, I’m married to your brother, Cain Brain. Well, not really married, not proper. We hitched up in a cloudy week in Nevada, cloudy from jazz and gin and a hot streak on the bones. But then on our honeymoon…well, an old pal of his came by with a basket of pears, roses and a pile of cocaine like Mt. Shasta, and he and Cain left the next day, ably stealing a bulldozer, wearing a gorilla costume and riding off into the desert singing “Old man River.’ Never did see him since.”

“That’s a tough break, Sugar Loaf. Wait, I got a brother named Cain?”

“You don’t know your own brother?”

“Fresh out of family since my Mom dropped me off at a Chicago hospital with the meter on the carriage running. ” I felt something in my stomach. A churning, buzzing sensation: maybe misguided bees. More likely a result of an empty glass. If the same thing happened in a regular joker’s stomach they’d call it an emotion.

“Listen, why do you think I’m one of the rich Brains?

And here was the kicker:

“I got a copy of Cain’s birth certificate right here. Take a look for yourself,” she said, somehow emphasizing her cleavage. She had black gloves on and pulled the paper out of her purse like an obituary.

“See, right here ‘Cain Brain. Mother: Matilda Achmedenejad Brain, age 19, of Peoria, Illinois. Race: Scots-Persian, of Peoria. Father: Stanley Jerimiah Brain, Race: Caucasio-Beige. Age 59, residence: Lake, Illinois. Brothers: Augustus, age 1. Maximilian , age 2. (Deceased), she said, with emphasis.

“Deceased?”

“I figure she listed you as dead to make it easier for the family, giving you up and all. Never met a dead man, before, Brain!”, she said brightly. “See, Mack, whether Mr. Brain is your father or not, you ain’t dead, and we gotta case for the inheritance, and I got the key to that case,” waving the paper in the air. She wriggled her hips just a little, enough so that the idea drained right through Smart Thinky Brain, down through the Dumkoff pipe and dripped right into my next sentence:

“Alright, Babycakes, I’m listening.”

She put her lips so close to my ear I could hear her lipstick.

“They got Millions, Brain. MILLIONS. ” She whispered. “Think of it.”

I was thinking all right. Thinking about paying off the bills, like the grocers, and Crumples, and a half-dozen ice men all after me on various contracts with the mob, angry husbands, the Nazis of course, Mickey Rooney for some reason, oh yes, and Stalin, and also my hobby railroad dealer. I was thinking about the ponies. I was thinking about naked cheap girls in baths of expensive champagne. Thinking about retiring early to a swell estate in Marin, buying a couple of stock llamas and a fortified wine vineyeard and setting myself up with a dance-hall princess that looked pretty much like Babycakes here and scandalizing the respectable types with rowdy parties and random pistol fire. And I thinking about Veronica. Thinking all wrong.

Meanwhile, Shanky the steam auto-harp player was boiling over.

“Veronica! You gonna sing or what?” He said, glaring at me. It was starting to get irritating.

“Your boyfriend there better be admiring my hat,” I said.

“Not now, Shanky. Cool your heels,” she said. He’d walked over now, his face turning white with rage and general whiteness.

Shanky was in that special place where you think about striking out a meaty paw and all your personality disorders magically disappear. And so his fist flew. But he might as well have sent the Western Union yesterday. I caught his hand mid-flight, spun round fast, and accidently on purpose broke his finger. You could hear the snap.

Shanky shrieked, rolling around on the floor.

“Jeeze, why’d ya have to mess up Shanky’s hand? That’s his livelihood!, said Veronica, but after a glance she was still looking at me.

“Think of it as a gift to the Nine Muses.”

“What? Do you know how hard it is to find a decent steam autoharp player?,” she asked.

I just looked at her.

“How can you make less dough than what Crumples isn’t going to pay you?” I said.

“Barkeep’s a dirty old welcher, huh?,” she said, raising an eyebrow so perfectly parenthetical I’d have to describe it as an aside.

“Crumples? A dirty old welcher? Look in up the Encylopedia Britannica, Kitten. You could fill the U.S. Mint with his I.O.U.s. I suspect he personally got the Depression started.”

“Mebbe if you’d paid your consarned bar tab, Brain!” Crumples said.

“Show’s over, old man!,” she said, storming out, and I followed her. We stood out in the dark and the fog, the lights from the neon nightclubs playing off her creamy skin like cream pored over cream-colored satin spread tight over creamy mounds of delicious ice-cream. After a while gazing at each and lighting each other’s Luckys, our heads swimming with love-sick ditties and god-damned Christmas jingles, I looked at her: flowing blond locks, the little smile on her lips as she parted them just slightly. I landed a palm like a coyote on her swan neck and kissed her like it was the last stamp on my ration card.

We caught a cab back to my office on Sutter street, which was also where I appeared to live going by the hotplate under the typewriter and the pot smeared with Cream of Mushroom Soup filed under “M,” or “C,” and where, after I’d fumbled with the key while practicing for her bra, she passed out on the couch, and I also passed out on the couch. Except we weren’t passed out.

The real thing was the morning. Somehow everywhere I looked it was Veronica. It was Veronica at all angles: tidying up, kindly explaining divestiture of family assets, will executors, our life together, the will to execute, and all the while standing there remorselessly, and then there, filing something on the lowest drawer with kinetic verve, looking like Veronica the whole time. I didn’t just fall off the turnip truck, but with Veronica there radiating bodacious relativism like a Nietzschean lighthouse on my rocky sucker coast of a life, I was more rutabaga than Porterhouse.

I told myself I was just using her, just curious about my family, joking around about millions, goofing about a golden silver spoon set that had been denied me, the rightful eldest, that had been dumped as a loveless wee bairn in a flop hotel in Chi-town. All a big joke, right? Such is the power of a Veronica. I gotta hand it to her- this was an avalanche of a snow job. Sweet nothings and little jokes turned around like salt-water taffy sticking on the taffy-stretching machine of my heart. I was laughing myself into a tannery of fear and desperation and possibly skinning.

So I found myself deep in fist-waving, eye-pounding research at the Hall of Records, good cabbage gone on telexes and phone calls to Chicago, looking up a buddy at the Chronicle to go through their morgue. I went through all the press on Brain Sr. - he was loaded all right, but in those early years in Chicago it was all foggy and hazy and and yet it hit hard, like someone dropped a crate of gauze on your head. Stan Brain, President of Brain Industries Limited, into coal, meat, metal, markets and machines, might be Big Daddy Warbucks, or might not.

The week drifted on, the research deepening, an incomplete family tree developed. The money beckoned like a warm Winnipeg brothel in an Arctic blizzard, driving my work. It got crazy. At one point, I seemed to be related to Goering. Meanwhile, like all the greats, Veronica played on my greed. And on my couch, which was getting more action that the Mediterranean Theater, and in the meantime, I was building a case for my part in this family and counting their money at the same time.

I found myself asking her bad, bad questions:

“Babycakes, where’s the file on inheritance taxes?”

“Babycakes, say, what about a beautiful broad like you and me getting hitched some day?”

“Babycakes, why do you think Stanley might have a heart condition?”

I was an actor in dinner theater, knowing that the terrible production was going to close the place, but saying my lines right on cue. =

Then on a Thursday at City Hall, rain and wind poring gray outside, and the little room smelling like damp newsprint, mildew and whiskey, I found the police report for my brother, Cain Brain: dead in the mountains, found near Lake Tahoe, holding a gun, dressed in a white tie and tails and a sash and formal snowshoes. The gun had been fired, four times, the body had been there since…, since….

STAYED TUNED FOR MORE OF THIS EXCITING ADVENTURE IN THE RATHER NEAR FUTURE!